Bridge of San Luis Rey – Plans in the Universe

For what human ill does not dawn seem to be an alleviation?

– Bridge of San Luis Rey, Thorton Wilder (62)

In the Pulitzer prize winning novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, American author, Thorton Wilder, explores the circumstances leading up to the collapse of an Inca rope bridge in Lima, Peru on July 20, 1714 which hurled five unassuming bridge-crossers to their immediate deaths.

A friar who witnesses the bridge collapse and the last moment of life of the five people crossing sets out to prove through their deaths that life has a greater plan:

If there were any plan in the universe at all, if there were any pattern in human life, surely it could be discovered, mysteriously latent in those lives so suddenly cut off. Either we live by accident and die by accident or live by plan and die by plan. (Wilder 9).

I read the entire book in a day.

The simplicity of the story and characters’ lives heightened the significance of deeper more pressing questions about life and its greater meaning.

Some say that we shall never know and that to the gods we are like the flies that the boys kill on a summer day, and some say, on the contrary, that the very sparrows do not lose a feather that has not been brushed away by the finger of God. (Wilder 12)

Thorton Wilder’s gift for language is still evident, decades after the book was first published in 1927.

It was the hour when the father returns home from the fields and plays for a moment in the yard with the dog that jumps upon him, holding his muzzle closed or throwing him upon his back. The young girls look about for the first star to wish upon it, and the boys grow restless of supper.

With an almost romantic surrender, characters are forced to recognize that perhaps a life plan is nothing more than a hopeful illusion, and in the end, we are not nor ever can be fate’s director – instead we are just actors playing a role on a greater stage with no say in when we enter, when we leave and what will happen once we’re gone.

There would be no one to enlarge her work; it would relapse into the indolence and indifference of her colleagues. (Wilder 118).

But perhaps the most beautiful passage of the entire book is the last sentence, which is poetically true, but is missing the fact, that not only love, but Wilder’s written word, is capable of building bridges of survival between the lands of the living (today’s readers) and the land of the dead (the author, the book’s characters).

There is a land of the living and a land of the dead, and the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning. (Wilder 124)

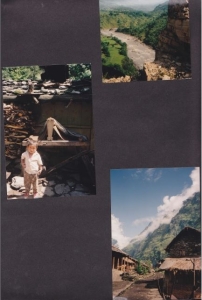

The book was first published in 1927 and I am thankful I didn’t get my hands on it till years after I had hiked the Annapurna Circuit in Nepal.

Hours of hiking in tropical heat and Alpine freezing temperatures, the weight of my pack cutting into the skin of my waist and shoulders, the cold water bucket showers, the blood sucking leeches, the soggy socks and boots that never dried or the back-to-the-basics outhouses – no problem. My problem was something else…

(Entry from my journal) Bamboo contraptions suspending rivers prove slippery and difficult to walk on – especially with a pack. If you manage to get past these without falling through or slipping off then there are still the suspension bridges. These architectural wonders dangle high above torrential rapids. They have been fashioned from rotting wood, skillfully saving the precious resource by only placing every second plank. Handrails, of course, have not made their way to Nepal. Who has the hands to hold on the handrails when you are lugging 5 times your weight across the bridges? Every time I place my first foot on one of these bridges, I say a silent prayer that no porters will get on the bridge from the opposite direction. All along the way we encounter these agile Sherpas practically skipping across the bridges hauling wooden cases loaded with bottles of Coca Cola or whole trees destined for firewood. Their weight invariably sets the bridge, my heart, and my stomach into a swinging pendulum back-and-forth number. So once I convince myself all is safe (relatively) I get up the guts to step on. But then I make the mistake of looking further down the river. Remnants of previous bridges that had probably given up just as a trekker was crossing, taunt me. What really are the chances of this thing caving in at the exact moment I am crossing, I repeat to myself as I go. I unbuckle my backpack. If I go down, I want a fighting chance and not to be swept to the bottom of the river by the weight of my pack. But a second more reassuring voice inside my head robs me of this illusion entirely. If the drop doesn’t kill you, the rocks will. If you manage that, you’ll freeze to death of hypothermia anyway. And if by some freak accident of nature you survive all that, the rapids will pull you under and drown you. So stop sweating it. If you drop, there’s nothing you can do anyway.

“We do what we can. We push on … as best we can. It isn’t for long, you know. Time keeps going by. You’ll be surprised at the way time passes.” (Wilder 74)

Read the Bride of San Luis Rey.The Bridge of San Luis Rey (Perennial Classics)

I don’t think you’ll be disappointed.